Smeerenburg

OUR ASPIRATIONAL DESTINATION

Getting to Smeerenburg had been our ultimate goal in Svalbard. It is located in the far north west of the archipelago on the island of Amsterdamøya . When we applied for the permit to cruise in Svalbard, it seemed far enough north for us and Yuma, with the probability of encountering pack ice significantly increasing further to the north and east. As it turned out we arrived a bit later in the season than we had planned and, by the time we had got there, the pack ice had already shifted well north. Another reason for wanting to get Smeerenburg though is that it was the centre of Dutch whaling operations on Spitsbergen during the 17th century and consequently it played an important role the Dutch contribution to Svalbard’s history. This has made it a significant site in the Dutch perception of their past and their contribution more generally. Furthermore, when at University in Groningen, I (Frederieke) had been lectured in Arctic Ecology by Louwrens Hacquebord, the lead investigator of the archaeological diggings conducted at Smeerenburg which had started in the 1970s. And both David and I had seen some of the results of these diggings at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. So plenty of reasons to go and see the real thing!

SVs Yuma and Saraban’de at anchor at Amsterdamøya.

GOING ASHORE

We had tried about a week before to go ashore at Smeerenburg, but at that time it was too windy to leave Yuma unattended in an unknown anchorage. But one morning during our stay at Virgohamna, the weather was suitable to cross the Danskegattet channel and anchor on the southern side of Amsterdamøya. We went across with Deborah and Matthijs from Saraban’de, which was extra special given that they are also Dutch and, similarly to me, had also never imagined that they would ever set foot at Smeerenburg. After a final look at the walrus-eating polar bear, which was just crawling out of the water at Virgohamna, we motored across in our sailing boats, anchored and launched our dinghies, all kitted out with our “going ashore” impediments.

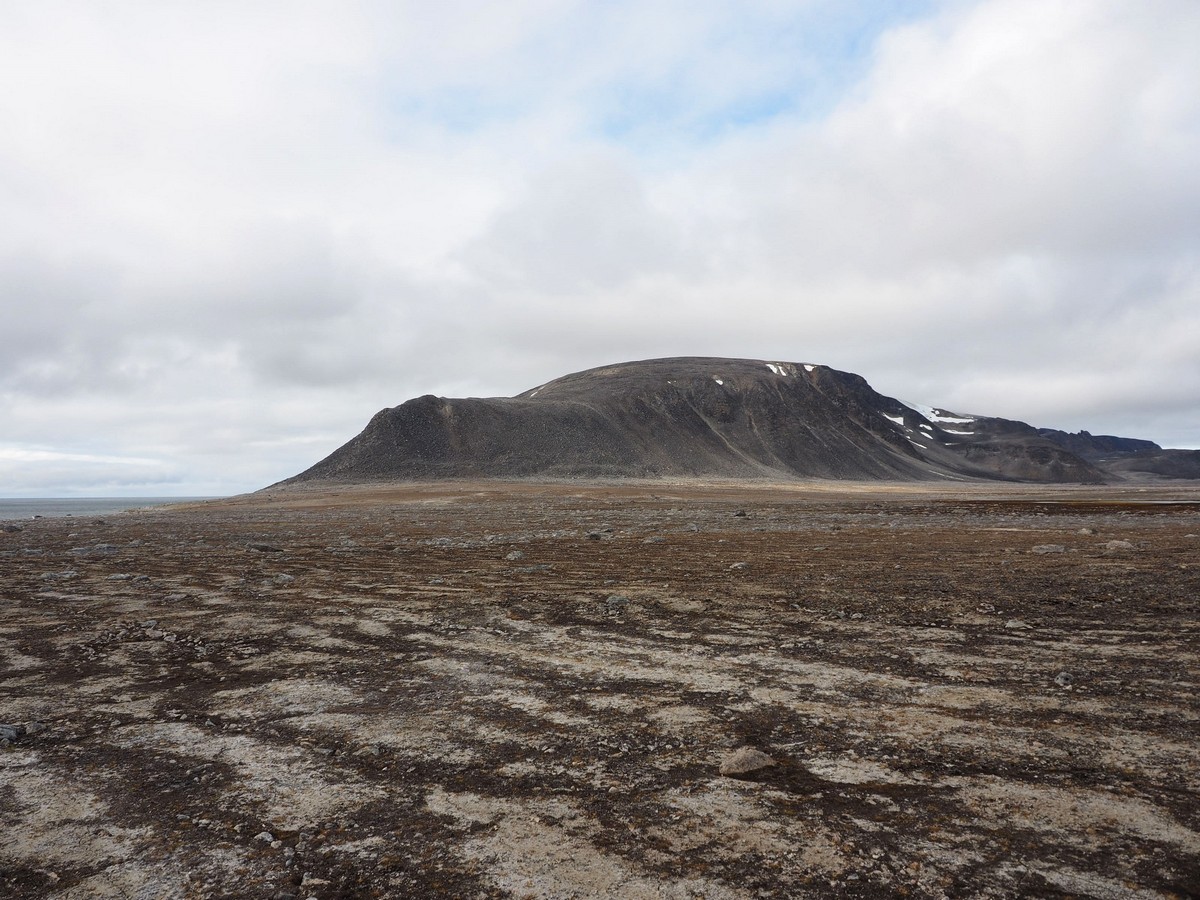

Looking west from Smeerenburg.

Ashore at Smeerenburg, with Deborah and Matthias.

A BIT OF HISTORY

After Willem Barentsz discovered Spitsbergen in 1596, tales of whale and walrus abundance along the coast and in the fjords flowed around Europe in the ensuing years. Of particular interest was the large (18 m) and heavy (20 to 30,000 kgs) Greenland right whale (now known as the bowhead whale). These were easy to catch, had a thick layer of blubber and lots of long baleen, and they floated when dead. These traits all added up to making them, indeed, the ‘right’ whale to hunt. Even better, these whales were so abundant that, in 1612, the seas around Svalbard were described as ‘being filled with whales around the sides of a ship’.

In the early 1600s, the Netherlands and England were the two main countries to establish whaling stations in Spitsbergen, and following their usual manner of engagement, they spent a lot of time fighting about whaling rights and the best hunting grounds. After a few years of stealing each other’s catches and equipment, and conducting a bit of minor warfare to top it all off, they finally agreed to act like adults and to use separate hunting areas. The English were assigned a hunting area south of the Magdalenefjorden while the Dutch got to work the area north of Magdalenefjorden. Other nations, such as Denmark-Norway, France, Spain and even the odd German city state also established whaling stations, but all did so at much smaller scales than these two countries.

In 1614 the Dutch had established a trade company, de Noordsche Compagnie, which monopolized the hunting grounds and waters around Spitsbergen. Several Dutch cities were involved in this company, namely Amsterdam, Hoorn, Enkhuizen, Delft, Harlingen, Veere, Rotterdam, Vlissingen, and Middelburg. Each city had its own independent trading chamber with separate facilities at Smeerenburg (and in the case of Harlingen, at Virgohamna on Danskøya, across the Danskegattet).

Lay-out at Smeerenburg. Each Dutch city operated a double try-oven (circles) and buildings (rectangular).

LOCATION-LOCATION-LOCATION

The whaling station Smeerenburg was founded by the Amsterdam Trading Company, probably sometime in the years just before 1620. This location was chosen as a suitable place to hunt whales because the waters surrounding Smeerenburg were calm with good anchorage for the whaling ships. The location was also accessible through multiple fjords and access was generally possible through at least one of these fjords in the eventuality that one or more of the others were blocked by pack or glacier ice. Most importantly, the surrounding seas and fjords contained large numbers of whales.

Every year whaling ships would sail from the Netherlands to Smeerenburg in late spring and stay until about August to hunt and process whales. The archaeological diggings showed that during first couple of years the facilities were temporary, but over subsequent years the town became more permanent. At Smeerenburg, each Dutch city had their own try-works (blubber oven) and buildings of wood and brick that functioned as accommodation, storehouses and workshops. To defend against competitors the town even had a small fortification! Every summer around 200 to 300 men would be involved in the whale hunting and processing. But at some point around 1660, Smeerenburg was deserted as the coastal whales had been hunted to extinction and whaling and whale processing moved to the open oceans.

Location-location-location.

Aside from its suitability for the business of whaling in the 17th century, the scenery surrounding Smeerenburg is astonishingly spectacular with fjords, glaciers and spiky mountains. This scenery would not have earned the Dutch any money at the time and would unlikely have influenced their decision to settle here. Had they known that the scenery now draws tens of thousands of tourists every year, no doubt the mercantile-minded Dutch would have kept Smeerenburg occupied to make another buck out of Spitsbergen. Instead, the spit on Amsterdamøya that once housed Smeerenburg is now occupied by a huddle of highly pungent walruses.

The current inhabitants of Smeerenburg.

SMEERENBURG TODAY

After we landed on shore, we first had a good look to ensure there were no polar bears to be seen. This time we had four pairs of eyes, two signal guns and two rifles – we all felt a bit safer in each other’s company! Given that we had been stuck on our boats for a while, what with a very lively polar bear around our anchorage, we decided to take the long walk to Smeerenburg across the flats to the other side of the peninsula. This would also take us blissfully upwind of the walrus huddle.

Remains of whalers’ graves.

Remains of whaler’s grave.

This detour took us through some interesting tundra landscape, as well as past some polar bear tracks and some old whaler graves that were located far outside the town boundaries. Whether these were the original whaler graves, or graves that were moved for preservation purposes at the behest of the Dutch Queen Wilhelmina in 1908, we don’t know. The polar bear footprints were most definitely original, and enormous, but they looked a bit dry and were maybe a couple days old. Despite their apparent age we had a good look around and, not seeing the owner, continued our walk.

Polar bear feet are large, very large!

Scanning the surroundings for polar bears.

It turned out that the walrus huddle was closer to our planned route along the spit than we had guessed from a distance, more like right on it than near it, really. We discussed what to do. Shall we walk past them, or would this be too close and we’d disturb them? According to Svalbard regulations ‘interfering’ with wildlife in any way, including disturbing them, is not allowed. After a bit of back and forthing, I took the lead and slowly crept behind the walrus to the other side where Smeerenburg the town used to be. We should not have worried; these enormous blobs of fat were not the least interested in interrupting their slumber for us. They kept snoring and belching away at each other, pushing each other this way and that to get even more comfortable on their haul-out, and did not take a single look in our direction. We, on the other hand, had a fantastic close look at walrus!

Such weird animals!

Past the walrus, we finally arrived at the remains of Smeerenburg. The try-ovens and houses owned by the individual trade chambers used to be located in a row, with Amsterdam in the east, Hoorn to the west, and Delft, Enhuizen, Veere, Vlissingen and Middelburg in between. In the 17th century, Amsterdam had the best location but now their buildings and facilities have completely disappeared into the ocean. Middelburg was next in line and is already well on its way to being washed away. The best remains were from Hoorn with the double try-ovens and house foundations still clearly visible.

At the remains of Hoorn try-works.

Try-works in various stages of disrepair.

It was absolutely amazing to walk around this historical town that we all had heard so much about! On the other hand, it was also very sad to realize that the Greenland Right Whale population had been cooked to extinction here. Four hundred or so years later it is still very, very rare to see one of these whales in the waters surrounding Spitsbergen.

Bijzondere expeditie. Een mooi zo’n historische sensatie in zo’n door natuur gedomineerde omgeving. Prachtige foto’s ook weer.

Dankjewel! Inderdaad een heel speciale ervaring om dit te kunnen zien.