Our first pile of rocks

More tidal streams

Our departure from Lézardrieux was an early-ish one with lines dropped at 0600 to ensure that we caught the best of the tide down the river. A soft grey light began to lift our surrounds from the sharp darkness as we cleared the river mouth and past the seaward end of île-de-Bréhat to clear the shoals of Les Héaux-De-Bréhat.

Early morning leaving the Trieux river.

As the light thickened, we could see some impressive tidal streams inside the shoals; clearly, we’d done well to stay north of the lighthouse. With a light NW wind, we beat offshore for 5 or 6 nm watching a bevy of big boats steadily gaining on us, sigh.

Clearing the shoals.

Heading west towards Terenez.

Out here the tidal streams were still strong and saw us pointing in the right direction but making way towards Falmouth (UK) over the ground. So, we cut back in and tacked through the channel behind île Bono and then, with the turn of the tide, we caught a lovely tide assisted run SW past Locquémeau.

Clearing the final headlands towards our anchorage.

A couple more tacks had us slipping into the bay at Terenez where we dropped anchor for the night.

Not a bad view from our anchorage.

Tumuli, dolmens and menhirs

Here at Terenez our objective was to visit the Neolithic tumulus on the Pointe de Barnenez.

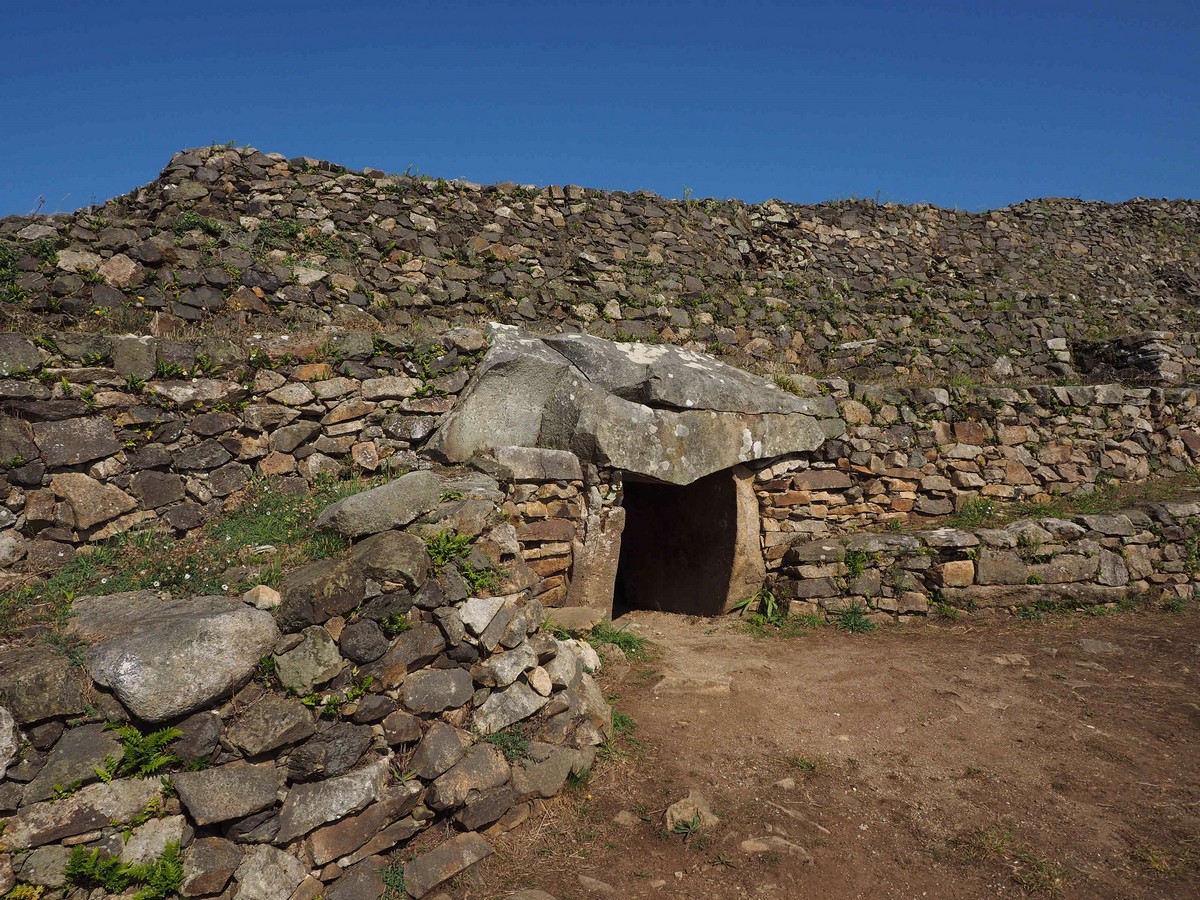

Le grand cairn de Barnenez.

One of the delightful things about Brittany is that it is chokers full of megalithic structures from Europe’s middle and late Neolithic period. Many of these are associated with burials, e.g. the tumuli and different types of dolmens, but others are of uncertain purpose, such as the isolated menhirs and the puzzling arrays of ‘standing stones’. The stones used in the construction of these features are generally big, like tons and tens of tons big, though some are hundreds of tons. These stones are thick slab-like things that, at least in the late Neolithic, were often worked and carved. In the case of dolmens (or hunebedden in Dutch) the stone slabs were stood upright to make corridors and chambers, covered with other slabs to enclose them and are then buried under earthen mounds. Tumulus are similar but are much larger and often have multiple ‘dolmens’ inside them. These were first buried in dry-stone mounds before these being buried again in earth mounds. The internal burial chambers often have worked and carved slabs lining both their interior walls and the interiors of corridors that approach them.

Entrances to separate grave chambers in the cairn.

Le grand cairn de Barnenez

We have previously visited a number of hunebedden in the Netherlands but these were all very disturbed and damaged. We had, however never seen a complete tumulus. Le grand cairn de Barnenez was our first chance for this and, despite the fact that you can’t enter the chambers, it didn’t disappoint.

A ‘dolmen’ inside the cairn.

Sure, it’s just a terraced mound of dry stone work but when you look at the detail of the construction, in particular in the partially quarried western section where three of the chambers have been half removed, you can see exactly how they have managed to make the beehive arches of the chambers themselves.

The beehive structure of one of the chambers.

Even better, the three partially exposed chambers were constructed over a period of the 1500 years and as a result you can see the evolution of the methods used, from interior finishings that are simple stone slab constructions, to a mixture of slabs and dry stone, to primarily very neat drystone work. Fascinating.

Different parts of the grand cairn de Barnenez.

Mola mola

Our visit to the Barnenez tumulus done, we packed up the boat and headed off in the late afternoon to make the short hop to Roscoff. Our departure from the Terenez bay was graced by a small ocean sunfish (Mola mola) swimming in that lopsided, lackadaisical mola-mola kind of way. This guy was probably only 70 or 80 cm across, but was happily motoring off into the bay, one fin half out of the water but still sculling away. What a treat to see one like that, even more so with the water clear enough to see the whole fish!

We just enjoyed our brief encounter with the mola mola, so no photo.

Susanne and I were captivated by the Newgrange passage tomb (and others in the area) along the River Boyne west of Droghedra in Ireland so I can appreciate your fascination with Barnenez.

Lucky you. These tombs are pretty simple things but somehow they are just fascinating. Perhaps, its just all the time that has seeped through them. Newgrange would be high on my list were I ever to make it to Ireland.